"Still in the Dark" was the culmination of a monthslong investigation into hazing at universities in South Carolina. It came after years of personal intrigue, both as a college student and as a journalist reporting on hazing incidents as they would surface.

Early in 2024, I learned the 10 year memorial of the death of Tucker Hipps was that fall. Tucker was a Clemson University sophomore who died during an early morning run with his fraternity brothers and other pledges. What happened that morning is still unclear, but his family believes he was the victim of a fatal case of hazing.

The project was a collaboration between Post and Courier Education Lab reporter Ian Grenier and I. I took the lead on writing the primary narrative throughout the mainbar; spoke with the Hipps family, several experts and officials; and reviewed public records from Clemson University, Coastal Carolina University and some smaller colleges for color throughout the piece.

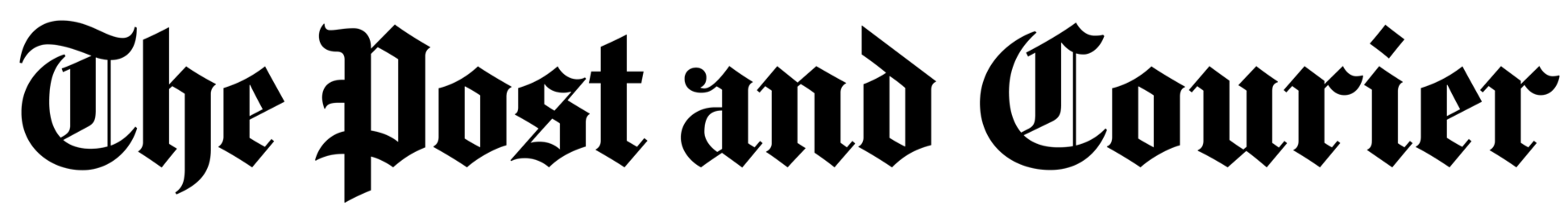

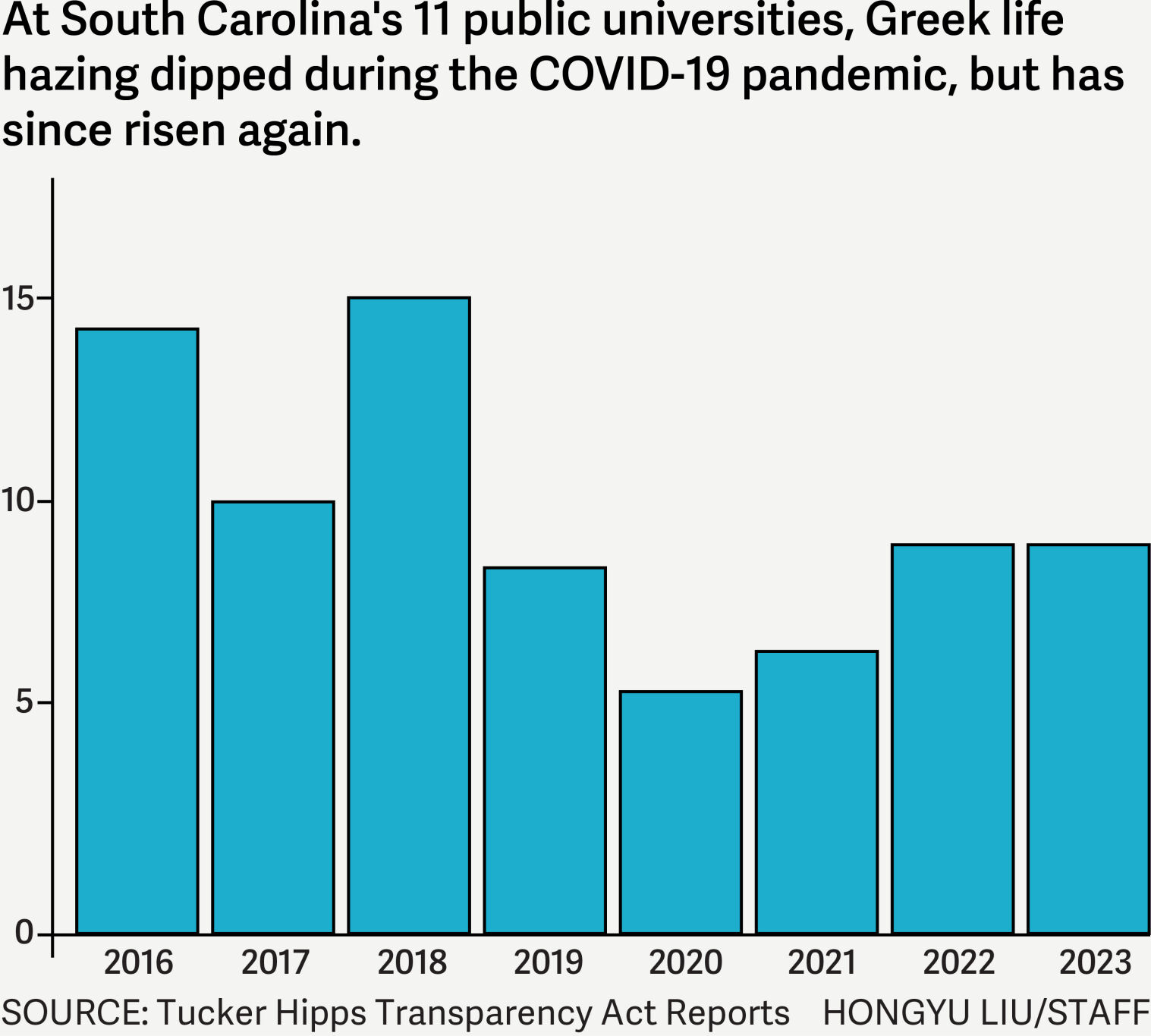

Ian and I both compiled each South Carolina university's records into a database, which I then formatted and presented using Datawrapper.

The sidebar was a co-byline between Post and Courier Clemson reporter Caitlin Herrington and I. Caitlin spoke with Oconee County authorities about the status of the case, while I added in context from the mainbar about the state of the case and timeline.

I shot all of the art featured in the mainbar, sidebar and database, with exception of two charts created by The Post and Courier's graphics team.

Use the three tabs below to view the three pieces of the project.

10 years after Tucker Hipps’ death, hazing is still alive at SC universities

Sept. 29, 2024 | OriginalOn an early Monday morning 10 years ago, a group of 30 Clemson University fraternity brothers and pledges ran across a bridge near campus.

Among them was 19-year-old Tucker Hipps. He had pledged the Sigma Phi Epsilon chapter in the hope it would help him pursue a career in politics. But something happened as the group crossed the Highway 93 bridge, sending Tucker plunging into the water below.

The fall proved fatal.

In the decade since her son’s death on Sept. 22, 2014, Cindy Hipps has pieced together a still-incomplete picture of what unfolded that morning. But after years of litigation and the case growing cold, no arrests have been made, nor has anyone come forward to confirm what happened to her son.

Cindy Hipps poses for a photo with her son Tucker Hipps in his room, largely the same as it looked before his 2014 death 10 years ago. David Ferrara

Cindy Hipps poses for a photo with her son Tucker Hipps in his room, largely the same as it looked before his 2014 death 10 years ago. David Ferrara

Witness testimony revealed that as pledge class president, Tucker was responsible for mistakes other pledges made. For that morning’s run, the fraternity brothers’ breakfast wasn’t up to par. Tucker’s parents believe he fell to his death after being forced to walk the bridge railing as punishment.

But for Cindy and her husband Gary, the prospects of ever finding out the full truth have grown dim.

“I don’t think they purposely killed him, but I think they know exactly what happened to Tucker,” Cindy Hipps said. “I think they caused it, and I think they have lied and were deceitful and tried to cover it up. And I think they have to live with that.”

Tucker Hipps’ death, and his mother's activism, pushed state lawmakers to pass an eponymous law in 2016 requiring South Carolina universities to publicly report hazing and other misconduct from fraternities and sororities.

Those disclosures show hazing is still alive in the state a decade after the deadly incident at Lake Hartwell, even as the number of reported incidents has declined.

In 2023, an investigation found Clemson Theta Chi members forced students to drink gallons of milk to the point of vomiting. In 2021, College of Charleston Sigma Chi members were accused of gagging pledges with socks while hurling eggs and beer cans at them. In 2015, Coastal Carolina University Kappa Sigma members reportedly encouraged young students to drink and drive, causing one to end up in a pond.

The Post and Courier built a database using each school’s reports under the Tucker Hipps Transparency Act. It shows a total of 105 hazing incidents since 2014 — though it’s difficult to know whether that total captures the true extent of campus hazing, which by its nature is shrouded in secrecy.

To better understand the problem, The Post and Courier examined a decade’s worth of hazing reports; obtained investigative files through open records requests; and interviewed university officials, lawmakers and experts. Together, they reveal an inconsistent system among state universities for policing hazing, at times allowing national fraternity headquarters to investigate a local chapter, and discrepancies between how different schools share information about incidents with the public.

What’s more, state officials appear to do little with hazing reports that are gathered under the Hipps Act. They simply note the numbers and then move on.

A memorial cross for Tucker Hipps sits in the median on S.C. Highway 93. Each year, Tucker's parents and a collection of friends have met at one end of the bridge about the same time he died. David Ferrara

A memorial cross for Tucker Hipps sits in the median on S.C. Highway 93. Each year, Tucker's parents and a collection of friends have met at one end of the bridge about the same time he died. David Ferrara

‘Part of the sales pitch’

Hazing has been around for centuries, spanning many countries and cultures. Accounts date as far back as the 4th century, with reported hazing at Plato’s Academy in ancient Athens, one researcher says.

The practice continues today at campuses across the United States.

Stories of South Carolina fraternity pledges eating disgusting concoctions, drinking copious amounts of alcohol or being subjected to dangerous quizzing rituals are real, Tucker Hipps Act reports and internal records show. But they don’t tell the full story of pledging a fraternity.

Technically a crime in South Carolina, hazing can range from making pledges do household chores to physical violence and forced alcohol consumption.

In one 2023 incident, Alpha Sigma Phi brothers at the University of South Carolina forced blindfolded pledges into a basement to quiz them about the group’s history. Those who answered incorrectly had to do squats, according to a university investigation.

In another, a Delta Tau Delta pledge at Clemson in 2020 spent the night in jail after a campus police officer found him drunk and locked out of his dorm in the middle of the night. He drank an entire bottle of tequila, was forced to do pushups on his knuckles in gravel and was compelled to do personal tasks for fraternity members, according to a report.

In defining hazing, state law focuses on incidents that cause physical harm or involve a “superior student” humiliating a subordinate.

Many schools have more expansive definitions. Clemson’s student discipline administrator Kris Adams defines hazing as anything required of new members but not of the full group.

USC and the College of Charleston also include acts such as forced servitude, exercise, public “buffoonery” and activities that are “morally degrading,” as well as required drug and alcohol consumption.

Max Marshall is a freelance journalist whose research into fraternities produced the 2023 book “Among the Bros.” It explored a 2016 College of Charleston drug bust that exposed a Southeastern narcotics ring in which frat brothers were key players.

Still, Marshall says the daily grind of being a pledge can be the most brutal part of joining a fraternity.

From sunup to sundown, and frequently in the middle of the night, pledges are expected to fulfill any brother’s request. Picking up food, finishing homework and doing laundry are what many experience during a typical semester as a pledge. Most keep a so-called “pledge pack” on them, a baggie with high-demand items such as cigarettes, dip or condoms.

It can be so intensive that some employers hiring recent graduates expect — and, in some cases, even respect — a slump in a fraternity member’s GPA during their freshman fall, Marshall said.

Some hazing exercises are designed for pledges to fail so they will have to face an unpleasant punishment, according to a 2016 paper by Aldo Cimino, a Kent State University professor who studies hazing.

Hazing becomes a perpetual cycle, with pledges going on to inflict similar abuse on recruits who come after them. It’s meant to foster a sense of brotherhood, even if, according to one study, there’s little evidence that hazing increases group solidarity.

In his reporting, Marshall found it’s rarely the case that students pledging a fraternity don’t realize they’re going to be hazed.

“(Hazing) is not something that people are getting tricked into doing. It’s something that people willingly go into,” said Marshall, who himself rushed a fraternity at Columbia University.

But it can be the final days of pledging, sometimes called Hell Week, when the temperature is turned up to high.

Tucker Hipps died after falling from the S.C. Highway 93 bridge at about 5:30 a.m. on Sept. 22, 2014. David Ferrara

Tucker Hipps died after falling from the S.C. Highway 93 bridge at about 5:30 a.m. on Sept. 22, 2014. David Ferrara

‘He made a fatal mistake’

The only child of two high school sweethearts, Tucker Hipps was close to his parents.

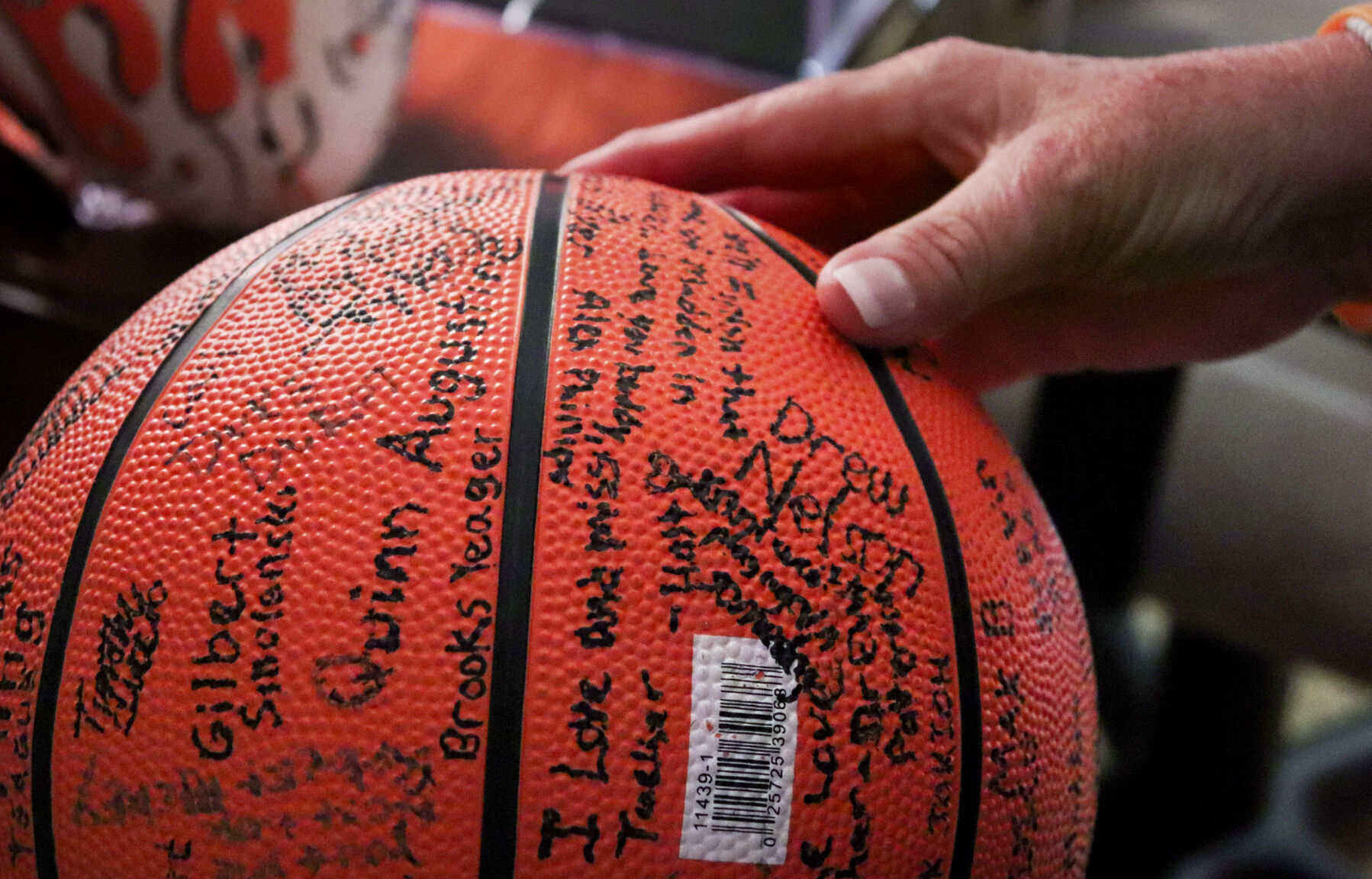

Tucker was a sociable teen, his parents recalled, carrying with him in life a strong faith and a sharp intellect. Regular basketball games with his father helped fuel a competitive spirit.

“He didn’t want to lose to me," Gary Hipps said. "He was always a smaller kid, and he always wanted to be a bigger kid.”

In the summer before his senior year at Wren High School in Anderson County, Tucker spent a week at Palmetto Boys State, a selective leadership program designed to teach kids how government works. He came back determined to attend law school and chart a path into politics.

In the political sphere, it’s all about who you know. Eighteen presidents and a majority of senators and Supreme Court members have been members of fraternities. Tucker saw the future value of being part of Greek life on campus and, despite his father's reservations, decided to rush.

“He made a fatal mistake when he got to Clemson," Gary said. "His desire for just being that person overshadowed his better judgment."

The rush process begins with attending various, open-invite events — parties, tailgates, kickbacks. If they’re lucky, those rushing might receive a bid, an invitation, for that fraternity.

Bid selection can be a ruthless process. Traditionally, brothers place a student’s picture before the group and share information about them. One objection can knock a student out of the running.

Soon after the fall 2014 semester began, Tucker received a bid from Sigma Phi Epsilon, commonly known as SigEp. Then, the grittier side of joining a fraternity began.

His parents suspected he was being hazed but didn’t know the full extent of it. Cindy Hipps recalled one incident that occurred about two weeks before his death.

At a noon football game against South Carolina State, Cindy and Gary waited at a tailgate for Tucker and his girlfriend, Katie Clouse. The couple arrived angry at one another, and Tucker wore a coat and tie drenched in sweat. He drank every bottle of water they had.

Tucker told his mom he had to set up the tailgate for his fraternity brothers and played some basketball before seeing them.

The truth, Cindy later learned, is that Clouse spent the night awake by Tucker’s side, worried he had been drugged at a fraternity event. Blindfolded and escorted into a room, Tucker had to recite his fraternity brothers’ names and hometowns correctly or drink alcohol, Cindy said.

By the time Cindy learned of the episode, Tucker was already gone.

The fraternity soon was kicked off campus after Clemson said it found evidence that pledges were required to buy drugs for brothers and give people rides. The frat cleared out, leaving a host of unanswered questions about Tucker’s death and the hazing he endured.

After 10 years, Tucker Hipps' room looks largely unchanged. The only child of two high school sweethearts, Tucker was very close to his parents. David Ferrara

After 10 years, Tucker Hipps' room looks largely unchanged. The only child of two high school sweethearts, Tucker was very close to his parents. David Ferrara

Transparency

In their search for answers, Tucker's parents pushed for greater transparency about hazing in South Carolina. Their efforts helped shed light on the abusive practices that continue to play out on the state’s campuses to this day.

Originally signed into law in 2016 and made permanent in 2019, the Tucker Hipps Transparency Act requires the state’s public four-year colleges and universities to report fraternity and sorority student conduct violations involving alcohol, drugs, sexual assault, physical assault and hazing.

The reports must include relevant dates, a general description of the incident, the charges lodged against the organization, the institution’s findings and the sanctions levied.

Other states have similar reporting laws, including Ohio’s Collin’s Law, Pennsylvania’s Timothy J. Piazza Anti-Hazing Law and Georgia’s Max Gruver Act.

On the federal level, a bipartisan bill that would require schools to annually report hazing incidents passed the U.S. House of Representatives on Sept. 24 and is headed to the Senate. Unlike South Carolina’s law, which only applies to public universities, the bill would apply to all schools participating in federal financial aid programs.

The South Carolina data suggests a downward trend in reported hazing incidents from peaks in 2016 and 2018. But it’s difficult to know for sure, given the potential for unreported incidents and the differences in how schools classify misconduct.

Schools have to post their Tucker Hipps Act reports online and report them to the state Commission on Higher Education on a semesterly basis — but little happens after the commission receives those reports.

During the most recent Sept. 5 meeting, commissioners spent less than 30 seconds presenting the annual report and only read off the number of violations. A review of meeting minutes since 2019 shows little to no discussion about the reports. The commission is not required to share those results with the Legislature.

Some universities disclose more than what's required by law, reporting incidents involving non-Greek life organizations, such as student government associations or club sports teams. Some include incidents not covered by the act, such as not following pandemic restrictions.

Unsurprisingly, the state’s largest campuses at Clemson and USC report the most hazing, but every campus has had some incidents, with the exception of USC Beaufort’s two sororities.

Delta Chi brothers at Clemson, for instance, were recorded by a bystander whistling, yelling and berating pledges to “keep running” and perform different exercises near their house in 2015.

Several fraternities have chapters at multiple schools, with each having been found to have hazed members repeatedly over the past 10 years. Pi Kappa Phi, which has chapters at Clemson, USC, Coastal, College of Charleston and other schools, has been found in violation of hazing policies nine times, according to the data.

For a particular chapter at a single school, the worst violator is USC’s Kappa Alpha Order, which has had five violations since 2012.

The reports offer the public some insights but can also be vague on details.

One typical description in a USC disclosure notes only that “information was provided to university staff alleging hazing concerns” and “an investigation conducted by the university determined concerns related to inappropriate activities in the new member education experience.”

Other universities provide more specifics. Clemson’s reports explain what types of hazing were found, such as the line-ups, ice-water baths and bodily harm inflicted on pledges at its Alpha Gamma Rho chapter in April 2023.

A USC spokesperson said the university’s reporting practices are similar to those of other state schools and “would be deemed to include a general description of the incident.”

The Commission on Higher Education seems to agree, with a spokesperson telling The Post and Courier that schools meet the reporting requirements.

The law also only requires universities to disclose misconduct by organizations, not individual students.

Recently, Clemson has started charging individual students with hazing instead of the entire group as a way to encourage reform from within. Adams said the school tries to determine whether it’s just a “couple of people” in the chapter who are involved.

In 2021, five Kappa Alpha brothers at Clemson hazed a peanut-allergic pledge. The brothers had the pledge buy some boiled peanuts, which they then pressed tightly to his skin with plastic wrap, according to an incident report.

Clemson did not list the incident on its Tucker Hipps Act report because it determined the fraternity itself was not responsible, the university said.

The brothers, who told police they didn’t know the pledge was allergic, did not face charges because there was no “intentional” harm under the state’s hazing law. The pledge, who later opted against rushing the fraternity, wanted the whole incident put to rest for fear of retaliation.

Prevention and enforcement

In the years since her son’s death, Cindy Hipps has spoken at universities across the state about hazing. Most of the time fraternities invite her to talk. Cindy spoke with Clemson’s Greek life students earlier in September, but said she is uncertain whether her effort made a difference.

University administrators stress they're working to stop hazing before it happens, driving them to deliver speeches, require anti-hazing training and provide chapter leaders with “targeted education."

Such efforts also are made by national fraternity headquarters. Every fraternity or sorority at the College of Charleston, for instance, requires internal hazing prevention education, the college said.

Wynn Smiley of Alpha Tau Omega, which has chapters at the College of Charleston and Clemson, said everyone who accepts a bid is required to take an online course about hazing, as well as alcohol and drug use. It’s meant to be “empowering” to new members, encouraging them to avoid hazing and assuring them they won’t be booted from a chapter for refusing to participate.

“It’s not their responsibility, certainly, if they’re put in that position,” said Smiley, who leads the national chapter. “But they need to understand that if they do, then we encourage them to say, ‘No, we’re not going to put up with this.’ ”

Dr. Louis Profeta, an emergency room doctor, was not shy with students in Greek life during a Sept. 16, 2024, talk about the deadly impacts of hazing, alcohol and drugs. David Ferrara

Dr. Louis Profeta, an emergency room doctor, was not shy with students in Greek life during a Sept. 16, 2024, talk about the deadly impacts of hazing, alcohol and drugs. David Ferrara

When complaints are made, the state has no universal standard for universities and national fraternity headquarters to investigate hazing.

Each institution has its own investigatory procedures and enforcement policies. Sanctions also vary, and can include required education sessions, restrictions on chapter events, recovery plans and a probationary period.

Repeated, severe misconduct will get a chapter kicked off campus, usually for four years, so that its current membership can cycle through school before it returns.

An incident from September 2023 sheds light on USC's handling of hazing complaints.

School officials received reports that Phi Kappa Sigma pledges were blindfolded with pillowcases, transported to undisclosed locations and forced to drink a mixture of non-alcoholic beer, cigarettes and raw eggs.

University police later responded to an anonymous call about hazing and found 20 men in a basement covered with rice. Five more were hiding in a bathroom with wet shirts. They initially denied being part of a fraternity but later acknowledged they were pledges at Phi Kappa Sigma, according to an incident report.

The university formed what it calls a “critical incident investigation team” of university staff to investigate. It determined through interviews that the chapter was hazing pledges by forcing them to clean brothers’ houses and requiring them to perform the task of picking up rice one grain at a time.

Investigators didn’t turn up any information about pillowcases, blindfolding or odious drinks. Interviewees denied any knowledge of that while giving contradictory answers about alcohol use. They maintained they were picking up the rice as a “funny joke” after it had been spilled days or weeks earlier by a drunk friend.

The report alleged that pledges were threatened with “potential physical violence” if they revealed anything about the ritual.

The chapter was put on probation until October 2026, and members faced educational sanctions.

Phi Kappa Sigma was one of two USC fraternities found to have hazed members during the fall 2023 semester, along with Alpha Sigma Phi for its blindfolded quizzes and calisthenics.

Fox guarding the henhouse?

When a fraternity chapter comes under fire, its national headquarters isn’t a call away. Its representatives are usually in the room.

At most campuses in the state, national fraternity representatives work alongside the university’s investigators or handle the complaints themselves.

When cooperative USC groups face less serious allegations, the national reps are allowed to run their own internal investigations and report their findings to the university rather than have the school handle the probe, according to Marc Shook, the university’s dean of students.

“There’s a big difference in an anonymous call saying something has happened versus a resident advisor who said, ‘I saw this happening with my own eyes,’ ” Shook said.

School administrators have to accept the headquarters’ investigation and findings before the incident is resolved.

Tucker Hipps loved basketball. After his death, several Sigma Phi Epsilon pledges and fraternity members signed a basketball and presented it to his parents. Many of those who signed it were on the run the morning Tucker died. David Ferrara

Tucker Hipps loved basketball. After his death, several Sigma Phi Epsilon pledges and fraternity members signed a basketball and presented it to his parents. Many of those who signed it were on the run the morning Tucker died. David Ferrara

The College of Charleston has used a similar “partner process,” as officials sometimes call it. The partnership between universities and fraternity headquarters can be one-sided at times, and some fraternities in the state have been allowed to investigate chapters faced with hazing allegations.

A fall 2023 investigation by Alpha Tau Omega partly cleared its College of Charleston chapter of hazing allegations reported to the national headquarters. It concluded that while alcohol was misused at a bid day event, members didn’t force people to drink, as one report alleged.

The fraternity’s headquarters also determined the sanctions the chapter would face, requiring policy reviews, additional alcohol education and the creation of a new recruitment plan.

It informed the chapter of its ruling over a month before telling college staff about the decision in December 2023, apparently prompting some confusion.

“I do hope it wasn’t sent to the chapter without a copy to us,” a college official wrote in November to the fraternity’s director of health and safety.

Still, college staff lifted a cease-and-desist order it had placed on the chapter without conducting an investigation of its own, with one official noting that “we will defer to HQ before we go deep in it.”

Alpha Tau Omega’s investigations include one-on-one interviews of students associated with the chapter, Smiley, the CEO, said. But headquarters staff is experienced enough to have a sense of whether reports and allegations “ring true,” he added.

“We’ll always follow up,” he said. “But depending on what we hear in that conversation, we’re approaching the investigation and follow-up perhaps a little differently.“

The College of Charleston said its staff is “always involved” when it receives the complaint first, and would not defer to a national organization’s judgment if it has clear evidence of violations.

The school's Alpha Tau Omega chapter again faced reports of alcohol-related hazing in the spring 2024 semester. That time, the investigation was led by college staff, who determined that “no evidence was found to support the allegations.”

South Carolina university officials and fraternity leaders largely dismissed concerns about fraternity headquarters’ involvement posing a conflict of interest. They said Greek organizations have a vested interest in expelling bad actors and protecting the fraternity’s pledges and reputation.

“The conventional wisdom by some is that everybody in the fraternity world is trying to say, ‘Oh, hazing is just boys being boys,’ ” Smiley said. “Nothing could be further from the truth.”

Each school handles the involvement of national fraternity groups differently.

At Francis Marion University, national groups conduct parallel probes into their chapters as the school does its own investigation. At Winthrop University, the national organization is allowed to participate in the process as the chapter’s advisor, but is otherwise uninvolved.

Clemson University's Donaldson Hall is one of several Greek life dorms on the school's campus, occupied by both fraternities and sororities. David Ferrara

Clemson University's Donaldson Hall is one of several Greek life dorms on the school's campus, occupied by both fraternities and sororities. David Ferrara

Several Tucker Hipps Act reports show national headquarters clearing South Carolina State chapters of hazing allegations, though a spokesperson said that the university’s student life office is “primarily responsible” for hazing inquiries.

Clemson officials say they get better results when national organizations are involved, since the groups have more educational and corrective tools than the school.

“They want hazing to stop,” said Adams, who heads Clemson’s student discipline office. “They really want that culture changed.”

Still, surveys suggest that “many, many, many” college students experience hazing, the hazing researcher Cimino said, a finding that’s incompatible with some administrators' and fraternity members’ notion that hazing often happens at the hands of just a few people.

In field work for his 2016 study, Cimino convinced an unnamed fraternity chapter to let him observe its hazing process. That included line-ups; physical exercises ranging from pushups and situps; and "ordeals" that "occasionally involve physical trauma," including exposure to cold, water intoxication and long-running events.

“Let me tell you, it was the entire fraternity,” Cimino recounted. “It was not just a couple who are engaging in hazing.”

‘Why is it a pattern?’

Some state lawmakers have pushed for raising penalties as a way to break the pattern of hazing, acknowledging that the existing misdemeanor offense doesn’t have much bite.

Over the years, there have been at least three attempts to pass a law upgrading hazing to a felony offense and spelling out qualifying behaviors.

None have passed legislative committees because of vocal concerns about how the change would impact rituals at schools like The Citadel, though many of the proposals specifically carved out exceptions for military training.

Another concern from lawmakers is where to draw the line on hazing.

Former Rep. Gary Clary, R-Central, participated in Greek life before graduating from Clemson in 1970. He admits standards have changed over the years, but hazing in his day never included daily chores or servitude. Other lawmakers draw distinctions between harmful rituals and those they say can “enrich a college experience.”

One of the most recent bills, proposed in January 2022 by state Rep. Jason Elliott, R-Greenville, and former state Rep. Westley Cox, R-Piedmont, lists activities like paddling, sleep deprivation or forced alcohol consumption as felony hazing. The bill called for a maximum 25-year prison sentence.

“With increased penalties, you send the signal that this is behavior that is not acceptable,” Elliott told The Post and Courier. “You are setting the tone for a campus culture that doesn’t condone hazing.”

Some, however, question whether the law is enforceable. The misdemeanor hazing statute has been on the books since 1987, yet records show there have been few students charged and even fewer convicted.

In one 2007 case, seven students were charged with hazing a Summerville junior at USC. The brothers allegedly used their fists, wooden paddles and a metal bat to beat the pledge during an off-campus initiation. The beating didn't stop, he said, until he was gasping for air and his nose was bleeding. Still, all of the charges were later dismissed, court records show.

In a 2021 case, three Francis Marion baseball players were charged with hazing that left one player with a broken jaw during a “reckless” drinking game. At least two of the charges are still outstanding.

Another concern is whether fraternities will just go underground. Clemson’s Pi Kappa Alpha was suspended in 2014 for violating a hazing-related punishment. The suspension was extended after the university learned the chapter was still meeting in secret, records show.

Hazing is inherently a secretive activity. When it goes too far, fraternities close ranks. Getting proper and sufficient evidence can prove to be a challenge, especially since greater proof is needed for a criminal conviction than a violation of a university’s policies.

“These cases are difficult because people don’t want to come out and be ostracized socially or blackballed,” said Adams, who spent 25 years as assistant solicitor in Greenville and Pickens counties before joining Clemson. “I think it’s a hard task to ask someone to out their friends or other people in a criminal realm.”

‘The grief doesn’t shrink’

Tucker Hipps died in the dark. It was 5:30 a.m., before the sun had begun to rise. The water below the bridge lay hidden in the shadows.

For the past 10 years, his parents and a collection of friends have met at one end of the bridge at about that same time. But this year felt different.

“As the years have gone by, it seems like now our scars are healing,” Tucker’s mom Cindy Hipps said at a vigil Sept. 22. “We still miss Tucker, and we’ll never not miss him, but it’s not as painful to come here as it used to be for me.”

Other than headlights from an occasional passing car, the only light came from candlesticks in the hands of 20 friends who prayed for Tucker and anyone who had lost a child.

“I would like to say that time heals all wounds, but that’s a lie,” Gary Hipps said. “The grief doesn’t shrink. Your life just grows around it.”

Tucker Hipps was an active, athletic kid, his parents recalled. All of his little league trophies and knickknacks still sit on his dresser 10 years after his death. David Ferrara

Tucker Hipps was an active, athletic kid, his parents recalled. All of his little league trophies and knickknacks still sit on his dresser 10 years after his death. David Ferrara

Back at the Hipps' house, Tucker’s room still has all of his knickknacks, little league trophies and photos, just as he left them in 2014. A collection of shot glasses grows, as Cindy gets Tucker one from every place she travels to.

Tucker’s 29th birthday would have been this past June. Every year, Cindy wonders what he’d look like and what he’d be doing. Getting married? Having a child? With friends and family, Cindy still talks about Tucker when others discuss their kids — but Tucker will be always 19 to her.

Cindy and Gary both say if they knew the truth they could have more closure. But no one from that day has come forward.

“They know exactly what they did, and they’re going to try to live out the rest of their life with that secret. And that’s fine. Go ahead,” Gary Hipps said. “I have to live with a mystery. They have to live with the truth.”

A decade after being found in Lake Hartwell, what do we know about Tucker Hipps' death?

Sept. 29, 2024 | OriginalCLEMSON — It's been a decade since Clemson University sophomore Tucker Hipps was found dead in Lake Hartwell, and what happened that morning still remains unclear.

The death of the 19-year-old who joined a fraternity, in large part, to pursue a future in politics is clouded with unanswered questions about what happened in the pre-dawn hours of Sept. 22, 2014. To this day, his name is synonymous in South Carolina with efforts to curb hazing in college fraternities and sororities.

To better understand the extent of hazing today, The Post and Courier examined a decade’s worth of hazing reports, obtained investigative files through open records requests and interviewed university officials, lawmakers and experts. Read the story and our findings here.

The Post and Courier also built a database using each school’s reports under the Tucker Hipps Transparency Act. It shows a total of 105 hazing incidents since 2014 — though it’s difficult to know whether that total captures the true extent of campus hazing, which by its nature is shrouded in secrecy. Check out the database here.

Here's what to know about Tucker Hipps.

What do we know about that morning?

Hipps and 29 others — three Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity members and 26 fellow pledges — went for a run around 5 a.m. that day.

They started near the stadium, according to Oconee County Sheriff’s Office Capt. Jimmy Dixon, and went along Perimeter Road to S.C. Highway 93.

The group turned around near the Highway 93 bridge over Lake Hartwell and headed back to campus.

Tucker Hipps died after falling from the S.C. Highway 93 bridge at about 5:30 a.m. on Sept. 22, 2014. David Ferrara

Tucker Hipps died after falling from the S.C. Highway 93 bridge at about 5:30 a.m. on Sept. 22, 2014. David Ferrara

Before heading back, Tucker's family believes that he, as pledge class president, was forced to walk the bridge railing as punishment for some of his fellow pledges' actions. He fell into the dark water below and died.

A fraternity brother called university police at 1:45 p.m., inquiring if Hipps had been picked up, but declined to formally report him missing.

Around 3:30 p.m., a university police officer retracing the route spotted Hipps in Lake Hartwell beneath the middle of the Highway 93 bridge, just a few feet away from where his memorial cross now stands.

Hipps had injuries that align with blunt force trauma and drowning, Dixon said. Historical data shows Lake Hartwell was 1 foot below its average level that day.

What happened after Tucker's death?

Following Tucker's death, his parents were looking for answers they say the police couldn't give them. They made the decision to sue Clemson University, the local and national chapters of Sigma Phi Epsilon, and the three fraternity brothers on the run with Tucker.

Tucker's dad Gary Hipps said they learned more about what happened that morning, but much of the testimony didn't seem truthful.

“We didn’t sue people because we just wanted to sue everybody and we wanted money," Gary Hipps said in an interview with The Post and Courier. "Money didn’t matter to us. We wanted the truth. Nobody was giving us the truth, and the only way to get these people to talk was to file a civil lawsuit against them and force them into depositions. All we got was just lies, lies, lies.”

The family eventually settled the suit, deciding the emotional anguish of lawyers attacking their son in court was too much.

The work it took to get answers inspired the Hipps to advocate for greater transparency surrounding university investigations of hazing. Their activism led state lawmakers to pass the eponymous Tucker Hipps Transparency Act in 2016, made permanent in 2019.

Each of South Carolina's 11 public colleges and universities now publish a report of misconduct by its fraternities and sororities twice a year.

A similar bill on the federal level, the Stop Campus Hazing Act, its headed to the U.S. Senate after passing the U.S. House of Representatives earlier in September.

Since his passing, Tucker's mom, Cindy Hipps, involves herself more in the community. She volunteers and leads Tucker’s namesake foundation, which hosts an annual golf tournament. She’s on the board of the local Crimestoppers unit, a national group that advocates for preventing and solving crimes. One of Oconee County Crimestopper’s unsolved crimes is Tucker’s.

“I always used to tell Clemson I’ll give it 10 years and then I’m done,” Cindy Hipps said. “But I’m not done.”

A memorial cross for Tucker Hipps sits in the median on S.C. Highway 93. Each year, Tucker's parents and a collection of friends have met at one end of the bridge about the same time he died. David Ferrara

A memorial cross for Tucker Hipps sits in the median on S.C. Highway 93. Each year, Tucker's parents and a collection of friends have met at one end of the bridge about the same time he died. David Ferrara

Are authorities still investigating Tucker's case?

Tucker's case is still open, Oconee County Sheriff Mike Crenshaw said, and will remain that way until the Hipps family has some measure of closure.

Dixon, who was the city of Clemson's police chief in 2014 and now works cold cases in Oconee County, said tips still come in and he’s in regular contact with the family. He and partner Barry Owens follow every lead, but nothing has resulted in discovering how Hipps ended up in Lake Hartwell.

“There are three people that I know, without a shadow of a doubt, know exactly what happened,” Dixon said. “My prayer is that, at some point in time, their conscience is going to bother them to the point that they're going to want to come forward.”

There is no statute of limitations in a death investigation, Dixon said.

No death certificate has been issued. The reason, Oconee County Coroner Karl Addis said, is because investigators all these years later have yet to determine a manner and cause of death.

Anyone who submits a tip to Oconee County Crimestoppers that leads to the cause and manner of death for Tucker Hipps may be be eligible for an award. Tips can be submitted at oconeesccrimestoppers.com or by calling 844-71-CRIME.

How many hazing violations got reported at SC colleges and universities? Our database has answers.

Sept. 29, 2024 | OriginalThe Post and Courier built a database of the 119 hazing violations that state colleges and universities have reported since 2011, as part of the newspaper's wider investigation into the state of Greek life hazing in South Carolina.

The 2014 death of 19-year-old Clemson student Tucker Hipps on a Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity run, and his parents' ensuing activism, pushed the state legislature to pass the Tucker Hipps Transparency Act in 2016.

Made permanent in 2019, the law requires state universities to publicly disclose fraternity and sorority misconduct related to alcohol, drugs, sexual assault, physical assault and hazing. Some schools have chosen to backdate reports, or report more violations that required by law.

This data helps show the breadth of hazing incidents in the past decade, and reveals the inconsistent levels of detail provided by different universities when they report organizations' misconduct.

Search through the database below.